Apart from aid, how are we doing?

I don't think it is possible to determine statistically whether aid makes a lot of difference to how quickly a country develops. But there is a very good case for aid on different grounds: that it enables people to live better lives in the meantime.

Though the effects of aid on development are uncertain, there is a huge amount that industrialised countries can do – or not do – which affects how quickly countries develop. The policies of rich countries on trade, investment, migration, the environment, security and technology can make a huge impact on how quickly poor countries are able to develop.

Yet we tend to judge industrialized countries too much according to how much aid they give, and too little to how they behave in all these other ways.

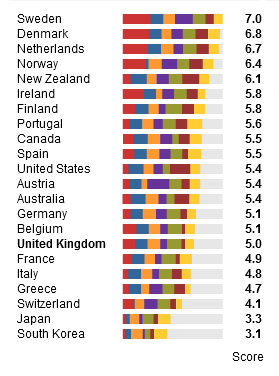

The Center for Global Development provides an essential service by ranking the rich each year so we can see how we are doing. They use a series of quantitative measures on all these dimensions to create a composite picture of how a country's policies affect development. The 2010 results are now in.

For people in the UK who feel smug about the UK's approach to development, the Commitment to Development Index makes pretty sobering reading. The UK is in 16th place, out of 22 countries in the index.

The UK has fallen ten places since 2005, when it was in joint fifth place, after only Denmark, Sweden, Netherlands and Norway.

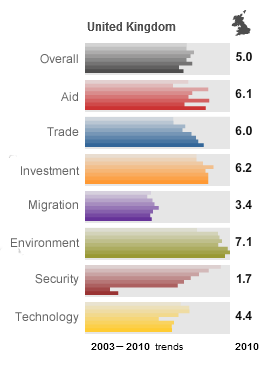

The UK is one of only three countries to have got worse rather than better since the index began in 2003. (The other two are Denmark – which started at the very top, and Switzerland.) And this isn't a point about the change of government: Britain was 16th last year too.

Given that the UK has a relatively generous and effective aid programme, why does it come so far down the league of overall impact on development?

In short: arms exports.

The Commitment to Development Index uses three measures of a country's security policy. It tallies the financial and personnel contributions to internationally mandated peacekeeping operations and humanitarian interventions. It rewards countries that base naval fleets where they can secure sea lanes vital to international trade. And it penalizes arms exports to undemocratic nations, on the grounds that putting weapons in the hands of despots can increase repression at home and the temptation to launch military adventures abroad.

The UK is by far the worst of the the 22 nations in the index on selling arms to poor and undemocratic governments. UK arms exports, weighted for undemocratic and unaccountable states, are four times worse, as a share of GDP, than the next worst arms exporter, the United States.

As well as being stand-out bottom of the pack on arms exports, the UK does badly on migration policy, because it takes too few unskilled immigrants and students for its size; and technology policy both because Government R&D spending is unduly focused on defence, and because the UK tends to pursue intellectual property rights policies that are not in the interests of poor countries, such as allowing patents on plant varieties, and pushing to incorporate into bilateral free trade agreements "TRIPS-Plus" measures that restrict the flow of innovations to developing countries.

Critics of aid often argue that we should focus more on helping countries to develop, rather than what they call "handouts' to poor countries. In that context, they usually mention the need for more open trade with developing countries. That is certainly important. The Commitment to Development Index suggests that they should also be advocating changes in UK policy to: reduce arms sales to undemocratic countries, accept more unskilled immigrants, increase the number of foreign students, remove patents on plant varieties and stop arguing for TRIPS-plus.

The UK gets credit for its environmental policies, mainly because it has done relatively well on limiting carbon emissions and because of high petrol taxes. Global warming has a disproportionately negative impact on developing countries, so these measures have an important impact on developing countries.

Many British people are proud of the UK's commitment to reducing poverty in developing nations, and Britain's model of an independent development agency within Government led by a separate Cabinet Minister is widely admired. But is it working? Judging by the scores in the 2010 Commitment to Development Index, the UK is doing a better job at securing and spending a rising aid budget than it is at getting the rest of government to pursue development-friendly policies.