Famine and drought

There is a famine in the Horn of Africa. I know there is a lot else in the news at the moment – the awful events in Norway, the US debt crisis, the British hacking scandal – but we need to keep this at the front of our minds. The situation is very bad. If you can afford it, you can give money in British pounds here or in US dollars here.

It is at times like this that we get a lot of half-baked commentary about famine. We are told that the problem is drought, or over-population, or global warming. Special interest groups call for more money to be spent on agriculture. Commentators complain that we've given aid for decades and nothing gets any better.

So here are two things to keep in mind.

First, famine is not caused by drought or overpopulation or insufficient food production. As Amartya Sen explained in Poverty and Famines, people go hungry when they cannot access food, because they are too poor or because markets and governments fail. Drought is neither necessary nor sufficient for famine.

Ed Carr says that this insight holds in the current crisis:

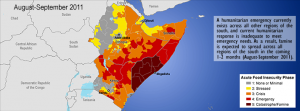

The long and short of it is that food insecurity is rarely about absolute supplies of food – mostly it is about access and entitlements to existing food supplies. The HoA [Horn of Africa] situation does actually invoke outright scarcity, but that scarcity can be traced not just to weather – it is also about access to local and regional markets (weak at best) and politics/the state (Somalia lacks a sovereign state, and the patchy, ad hoc governance provided by al Shabaab does little to ensure either access or entitlement to food and livelihoods for the population). For those who doubt this, look at the FEWS NET maps I put in previous posts (here and here). Famine stops at the Somali border. I assure you this is not a political manipulation of the data – it is the data we have. Basically, the people without a functional state and collapsing markets are being hit much harder than their counterparts in Ethiopia and Kenya, even though everyone is affected by the same bad rains, and the livelihoods of those in Somalia are not all that different than those across the borders in Ethiopia and Kenya.

If you are interested in learning more, read Ed Carr's book Delivering Development, and his blog. My colleague Charles Kenny makes a similar point in Foreign Policy.

Second, development aid works. Though there is considerable suffering, famine has been avoided in Ethiopia this time so far, and that is because of the safety net programme and disaster management system which has been set up by the Ethiopian government, with help from foreign aid. Remember 1984, and people leaving their land to make their way to feeding centres in Ethiopia? Not happening this time. Why not? Here's what the BBC says:

BBC Africa analyst Martin Plaut says many people at the heart of the current disaster – in Ethiopia – have emerged relatively unscathed. This is because the government in Addis Ababa has such an extensive safety net in place, he says. Pre-positioned supplies mean the Ethiopian authorities could respond rapidly once the extent of the drought became clear. The first food distributions began in February and have continued to the worst effected communities across a vast area. Communities are suffering, but the famine that has hit neighbouring Somalia has so far been avoided in Ethiopia and overall the disaster management system, built up since the 1980s, has worked.

Martin Plaut is no starry-eyed apologist for the aid system or the Ethiopian government. But like me, he was in Ethiopia in 1984 so he knows what famine looks like; and he can see the difference in Ethiopia this time. As he points out, the investments that have been made over the past two decades have transformed Ethiopia's ability to deal with bad rains. Ethiopia has suffered drought and famine about every ten years. But now a determined government, backed by foreign aid, has put in place systems which have made Ethiopia more resilient and prevented a repetition this time of past tragedies. If you are one of the Ethiopians who has put this in place, one of the hard-pressed development workers who has patiently assisted, or if you have contributed to aid, through taxes or donations, you should pat yourself on the back: bad as things are in the Horn of Africa today, the crisis would have been a lot worse without you.

Please spare a thought, and a few quid (or a few dollars) if you can afford it, for the 11 million people affected by hunger in East Africa today; and for the many aid agency staff working round the clock, often in difficult and dangerous conditions, to try to help them.