What’s a Big Government?

By James Kwak

One thing that all parties seem to be able to agree on is that big government is bad. It was President Clinton, after all, who said, "The era of big government is over." And the current Republican budget-slashing wave seems motivated by the idea that our government is too big.

But what is the size of government, anyway?* When a typical anti-government person thinks of government, she probably has in mind the EPA, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the "jack-booted government thugs" at the the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, OSHA, and all those government agencies that prevent businesses and individuals from getting on with their lives. The idea here is that government intervention in the free market makes the economy less efficient and therefore reduces aggregate societal welfare.

Another big part of the government is defense spending. President Reagan, the patron saint of "small government," wanted to roll back the regulatory state, but he very emphatically wanted more defense spending in order to "fight" the Cold War. Traditionally, conservatives have exempted defense spending from their budget-cutting axes, although to their credit some (though not Paul Ryan) have recently come around to the view that reducing the deficit will require cuts in defense as well.

Then there are entitlement programs, which are mainly composed of Social Security and health care (primarily Medicare and Medicaid). Social Security is unequivocally a government program (so is Medicare, "keep your government hands off my Medicare" notwithstanding), but it isn't government in the same sense as the EPA. Social Security is a mandatory retirement insurance program with a modest redistribution component, so it affects when people have cash and who has that cash, but it doesn't otherwise change economic behavior.

So where am I going with this? First of all, when you look at the data, it's not even clear that government has been getting bigger at all. This chart shows total government receipts and outlays for the past forty years and the next ten years. (All data are from the CBO's most recent Budget and Economic Outlook.)

If you look at the red line, what you see is that "government" appears to be getting smaller in the 1980s and 1990s, then starts growing again in the first decade of the 2000s (by FY 2007 it's already as large as it has been since FY 1994), spikes upward in FY 2009-2010 because of automatic stabilizers and (secondarily) the fiscal stimulus, and is projected to grow modestly after the stimulus subsides. So the "big government" story only makes sense, if at all, from FY 2002.

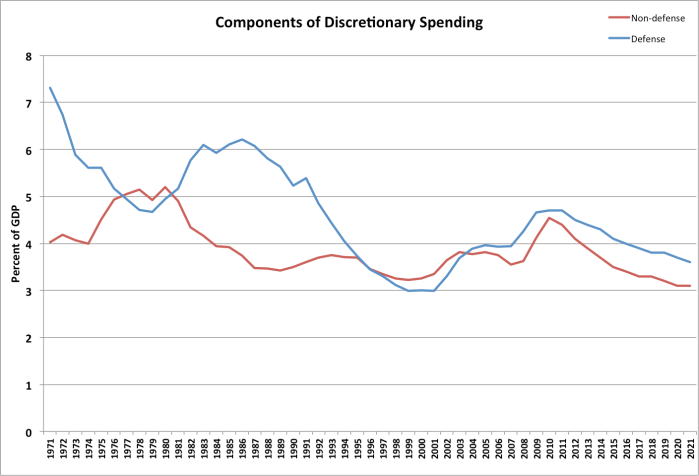

What's happened since then? This chart shows discretionary spending divided into non-defense and defense spending.

On the defense side, what you see is the buildup of the Reagan years, the peace dividend of the 1990s, and, starting in FY 2002, the increase in spending for Afghanistan and Iraq. On the non-defense side, you see Reagan's successful efforts to make government smaller, but since then non-defense discretionary spending has basically been constant, with bumps every time there is a recession.

For the period from 2001 to 2008, government in the EPA/ATF/OSHA sense barely budged. The vast majority of the total growth in outlays was due to increased defense spending (about 50 percent) and to Medicare (about 35 percent). The 2009-2010 spike in outlays was due partly to the stimulus, which erodes over time, partly to a big increase in defense spending, and mainly to increases in automatic stabilizers and Social Security (perhaps because of people exiting the workforce due to the recession).

When you look forward, the future growth of government outlays is entirely due to entitlements (and interest on the debt). Everything else that government does is getting smaller: in 2021, the CBO projects that defense spending will be at its lowest level since 2002 and non-defense discretionary spending will be at its lowest level in more than fifty years.**

So what can we conclude from this?

First, if you think of government as regulation of people's ordinary lives, that government has been getting smaller since the 1980s and continues to get smaller. In that sense, Reagan won, and conservatives who continue to complain about big government don't realize that they won already.

Second, if your conception of government includes national security, then you probably don't have too much to complain about. We spent a lot in the 1980s; spent a lot less in the 1990s after winning the Cold War; and spent more in the past decade for the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. I personally don't think that we should have invaded Iraq, but if you take that as given (and that was very much the doing of Bush II and Cheney), then the increased spending has been justified.

So the only sense in which we have "big government" that has been getting bigger is entitlements. And the key question here is: should increased entitlement spending count as bigger government? Here I say: not really. Obviously entitlements like Social Security are government programs, and Medicare is more intrusive into the private sector than Social Security. But if we accept Social Security and Medicare at some size, is the fact that their outlays are growing evidence that the government is getting bigger in any meaningful sense?

For Social Security, the answer is clearly no. Social Security's outlays to the individual beneficiary have remained constant, and so the amount by which those outlays or the promise of those outlays changes peoples' and firms' behavior is constant. The implications of a potential payroll tax increase are more complicated, but since those taxes haven't increased in decades, it's hard to say that government has been getting bigger because of payroll tax increases.

Medicare is also more complicated, but the basic principle is simple. Say in year 0 health care costs $100. In year 1 health care costs $110 (assume zero inflation). If Medicare outlays are 10 percent higher in year 1, is that bigger government? The first-order answer is no, because Medicare is buying the same amount of health care it was in year 0; so if we as a nation decided that Medicare was buying the appropriate amount of health care, then it is still buying the appropriate amount of health care. When you dig a little deeper things get more complicated because there should be some price elasticity of demand for health care, so if prices go up by 10 percent we as a society probably want to buy a little less than 10 percent more health care — maybe 8 percent more, since health care is pretty inelastic. So the point there is that Medicare should evolve toward better cost containment, which is basically the philosophy behind part of the Affordable Care Act.

Now, none of this is to deny that there is a problem out there somewhere in the future, since entitlement spending is currently projected to grow faster than revenues . . . forever. But the reason for that has nothing to do with "big government" in the classical right-wing sense of government bureaucrats telling freedom-loving Americans what to do. There are two basic reasons. First, our population is getting older, and we decided decades ago to create certain programs to help old people. Second, health care costs are going up rapidly. (And five minutes of comparative research will tell you that the best way to control health care costs is more government, in the form of a national health insurance program. The problem we have here is that the private sector determines the cost of health care but the national government is committed to buy a certain amount of it).

Of course, conservatives are jumping on the projected entitlement deficits to demand further cuts in the part of government they hate, mainly discretionary non-defense spending. But that "solution" has nothing to do with the problem we face.

* This post is vaguely motivated by the book I'm currently reading: The Age of Deficits: Presidents and Unbalanced Budgets from Jimmy Carter to George W. Bush, by Iwan Morgan. It goes into detail on all of the major budget negotiations of the past thirty-five years. (One reason I've been blogging less is that I'm trying to read more and write less.)

** I know there are problems with the CBO's baseline projection (the CBO knows it, too), but those problems are much bigger in areas other than discretionary spending. The big whoppers in the baseline are things like letting tax cuts expire, not patching the AMT, and not passing an annual fix to Medicare payment schedules.